New Earth 21

Image: アイデア IDEA Magazine. 1982

The year 1990 crackled with the energy of collapsing certainties. The Berlin Wall had fallen the previous November, Eastern European governments were toppling monthly, Nelson Mandela was released after 27 years of imprisonment by South Africa's apartheid government, and the Soviet Union was visibly disintegrating. Everything that had seemed permanent since 1945 was suddenly negotiable.

Environmental anxiety was becoming impossible to ignore. Two years prior, NASA scientist James Hansen had testified before Congress during a record-breaking heat wave, declaring with 99 percent confidence that human activity was warming the planet. His testimony made front-page news and brought “climate change” into public consciousness. The same year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was established. By 1990, the scientific consensus was solidifying around a problem that seemed to demand immediate action, yet required solutions that might take decades to develop.

Japan found itself economically ascendant but geopolitically constrained. Japanese banks dominated global finance, its GDP per capita had surpassed America's, and its companies were on a buying spree, snapping up U.S. landmarks from Rockefeller Center to Pebble Beach, yet it remained locked within the constitutional and diplomatic framework of the postwar settlement.

Into this uncertainty came a moment of grand thinking. Japan announced New Earth 21, a 100-year plan to clean up the natural environment that had been degraded by human industry.

In other words, a scheme to save planet Earth.

The timing and methods are worth examining. Three months after Japanese Prime Minister Toshiki Kaifu sat with six other world leaders at the G7 Summit in Houston, where they proclaimed the necessity to protect the Ozone layer, Japan proposed nothing less than global environmental restoration.

This wasn't summit rhetoric. The Research Institute of Innovative Technology for the Earth (RITE), founded specifically for the New Earth 21 program in 1990, was institutional infrastructure designed to address worldwide environmental challenges across an entire century.

New Earth 21 consisted of five interconnected elements: energy conservation, alternative energy, environmental technologies, international technology transfers, and systems analysis. RITE served as the coordinating hub, bringing together researchers, engineers, and policy analysts to work on these challenges simultaneously.

The institute operated within the broader context of Japan's systematic approach to foresight, including the government's KIDSASHI methods for long-term forecasting (which I explore in a companion essay). What New Earth 21 specifically contributed was building detailed scenarios for how these technologies might be deployed globally. Rather than pursuing isolated projects, New Earth 21 was designed as an integrated system where breakthroughs in one area would accelerate progress in others.

What Japan proposed seemed to defy the logic of democratic governance and the revolutionary moment surrounding it. While the entire geopolitical architecture was being redrawn, Japan committed to century-scale environmental restoration with concrete backing. This represented a fundamentally different approach from either military power or economic dominance: authority based on scientific capability and moral responsibility for planetary repair.

The scale was genuinely global. The Japanese program was proposing to reverse two centuries of industrial environmental degradation through innovation. Preserve tropical forests, restore atmospheric balance, develop clean energy systems, green deserts, and do it all while maintaining economic growth. New Earth 21 positioned Japan as coordinator of this planetary rescue operation, offering both the framework and scientific solutions needed to address existential threats.

Most environmental programs operate through predictable project cycles. Politicians announce targets, diplomats negotiate agreements, and everyone hopes something gets implemented before the next election cycle changes priorities. Japan flipped this approach —they built the machine first. Establish the research institutes, hire the scientists, create the analytical systems, then figure out how to deploy permanent infrastructure for century-scale thinking, globally.

The timing reveals both Japan's strategic place in the new environmental diplomacy and the remarkable range of approaches to planetary challenges that converged in Houston that summer.

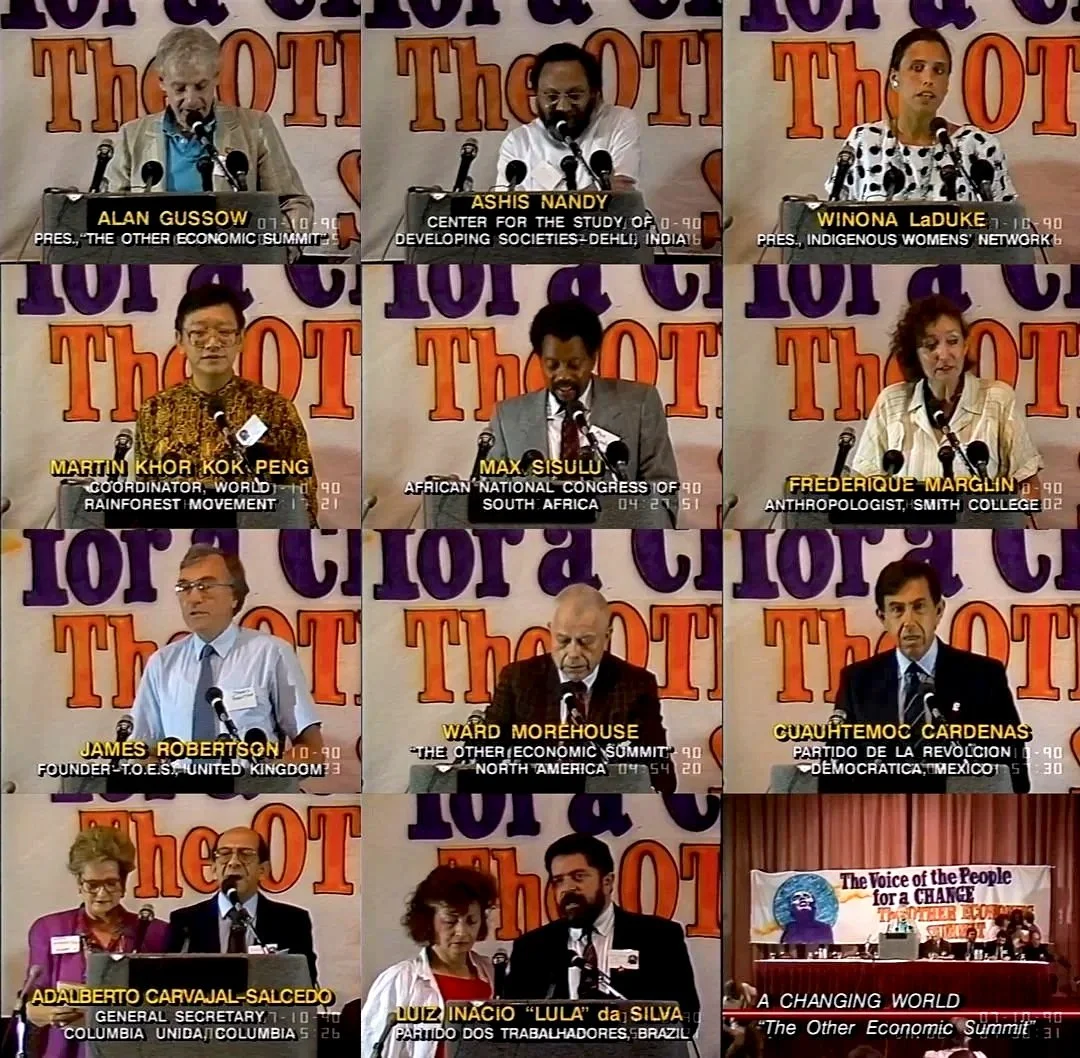

While the world's most prominent leaders gathered at Rice University and dined on tortilla soup at Bayou Bend mansion, on the other side of Houston at the modest Astro Village Hotel, a group of politicians, academics, activists, and populist leaders gathered at an alternative summit called The Other Economic Summit (TOES). The goal of TOES was to build an "international citizen coalition for new economics grounded in social and spiritual values to address concerns the G7 consistently neglects, such as poverty, environment, peace, health, safety, human rights, and democratic global governance."

Houston itself reflected this global ferment, made more intense by the sweltering July heat. Among the TOES guests at the hotel by the freeway was a metalworker named Luiz Inácio 'Lula' da Silva, decades away from becoming President of Brazil. The alternative summit was caught between competing demonstrations: a Cure AIDS Now rally that had narrowly avoided overlap with a KKK march, which faced off against anti-racist counter-protesters from The Human RACE (Racial Acceptance and Class Equality), featuring speakers such as former mayor Ray Hofheinz and NAACP representatives. Each group carried their own vision of America's future.

These grassroots movements, like their diplomatic counterparts, were increasingly thinking in global terms.

The contrast was telling. At least three different visions for addressing global challenges emerged from Houston in 1990. The G7 approach emphasised diplomatic protocols and international agreements. The TOES alternative focused on global organising and economic justice. Japan's announcement of New Earth 21 three months later represented a third way, one based on century-scale planning that transcended both diplomatic cycles and activist movements.

Why would a single country propose to solve problems for the entire planet? The impulse has a long history. Visionary individuals, international organisations, and ambitious nations have repeatedly offered grand solutions to global challenges, each reflecting their particular strengths and worldview.

Japan had been building toward this moment for years. Since the 1970s, it had refined sophisticated forecasting methods, including Delphi surveys, where panels of experts make repeated predictions about future technologies until they reach consensus. These techniques helped Japan anticipate which innovations to pursue and when they might become viable. South Korea adopted similar methods in the 1990s. Both countries used systematic future-thinking to guide their development strategies.

But planetary schemes extend beyond government forecasting. In the 1960s, designer Buckminster Fuller promoted his World Game concept, using early computer simulations to show how global resources could be redistributed to eliminate scarcity. The Club of Rome's 1972 Limits to Growth report used systems modelling to argue that unchecked development would hit planetary boundaries. More recently, scientists have proposed planetary boundaries frameworks that treat Earth as a single system requiring coordinated management.

Image: HMCJ / CSPAN. The Other Summit. 1990

Image: RITE in Kyoto / 公益財団法人地球環境産業技術研究機構

What these initiatives share is the assumption that global problems require "global solutions", though they differ dramatically in their methods. Some emphasise changing human consciousness, others focus on better resource management, still others advocate technological breakthroughs.

New Earth 21 was distinctive because it combined the institutional commitment of a major economic power with an exclusively technological approach. Unlike most planetary thinking initiatives that emphasise social transformation or consciousness change, Japan's program avoided the messy work of changing how people think. It simply offered to build the technologies that would secure the future.

The entire enterprise rested on a massive assumption that rational solutions would inevitably be adopted. If the technologies worked, if the economics made sense, if the environmental benefits were clear, then implementation would naturally follow. This reflects a particular view of how change happens in the world, one that sees human behaviour as fundamentally logical rather than driven by emotion, politics, or cultural inertia. It's the kind of assumption that makes sense on the designer's page, but becomes more questionable when you're trying to reshape how eight billion people will live.

The program emerged as systems analysis capabilities made planetary-scale modelling more feasible. Humans could now better calculate global environmental flows, model interventions, and project outcomes across century-scale timeframes. The analytical capability to think "planetarily" had arrived and environmental stewardship offered a pathway to moral authority that transcended traditional geopolitical limitations. Unlike foresight processes that are inclusive and accessible, ensuring that diverse perspectives are integrated from the outset, Japan could, through New Earth 21 and other efforts at RITE, subtly position itself as the world's environmental problem-solver through scientific excellence alone.

New Earth 21 embodied a technocratic faith that engineering solutions could transcend political divisions. Japan had found its own approach to global influence through innovation rather than confrontation or social transformation. The logic was appealing. Build better technology and political arguments become irrelevant.

This required an extraordinary leap. New Earth 21 was audacious because it committed to technologies that didn't yet exist. Japan was placing a century-scale bet on breakthroughs that remained purely speculative in 1990.

The gamble proved prescient. RITE went on to develop world-leading technologies for capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it underground, something that, in 1990, was largely theoretical. The institute also pioneered sophisticated computer models for analyzing global climate systems. While New Earth 21 didn't explicitly anticipate artificial intelligence, it recognized that managing planetary systems would require computational power far beyond what existed at the time.

Japanese leadership understood something crucial about planetary-scale environmental challenges. They would require solutions that hadn't been invented yet. Rather than limiting themselves to existing technologies, they built the institutional infrastructure to develop breakthrough innovations over decades.

Importantly, New Earth 21 contained virtually no social or cultural considerations. The program’s premise was that scientific solutions, properly developed and deployed, could address planetary challenges without requiring changes in how people actually live, think, or organize their societies. Implementation was an engineering task rather than a social one. In their presentations, getting people to actually adopt these technologies appears as a simple point on a slide, as if the hardest part was inventing the solutions rather than convincing the world to use them.

This reveals something crucial about the psychology of proposing global solutions (and where looking back thirty-five years on a plan to extract the planet from environmental demise becomes increasingly poignant). They often reflect the proposer's strengths rather than the problem's actual requirements. Japan proposed scientific solutions because Japan excelled at innovation. Whether the problems were primarily scientific, rather than social or political, remained a secondary consideration.

Cathedral thinking in a revolutionary time

Cathedral thinking is about planning across multiple generations rather than single lifetimes, rooted in the medieval church's approach to building sacred architecture that would not be completed in one lifetime. Japan applied this approach to planetary stewardship precisely when everything else was changing by the month. One would expect that most revolutionary moments produce short-term thinking and immediate responses to urgent crises. New Earth 21 did the opposite, creating the longest time horizon for addressing the ultimate long-term crisis.

The program's unusual name, either by coincidence or intention, hints at deeper currents. New Earth 21 echoes the biblical Revelation 21, which promises a "new heaven and a new earth" after the first earth has passed away. Whether consciously or not, Japan's century-scale vision of planetary restoration carried theological undertones that its purely technological veneer might not immediately suggest. The idea of systematically repairing a damaged world through human effort reflects themes that run deeper than engineering alone.

RITE has since achieved world-leading breakthroughs in carbon capture, bio-refinery systems, and climate modeling. Looking back, it is remarkable how rational the mandate of New Earth 21 was in 1990. The scientific capability existed. The institutional framework was built. The international cooperation mechanisms were established. The promise made at that Houston summit led to Rio in 1992, then to a succession of climate conferences: Kyoto 1997, Paris 2015, and dozens more. The feasibility was proven; the collective adoption was not.

New Earth 21’s premise stands out even more starkly today. While a few other century-scale projects exist, such as nuclear waste repositories designed to last 10,000 years, the Svalbard Seed Vault, and the Long Now Foundation's 10,000-Year Clock, most focus on preservation rather than active planetary management. New Earth 21 remains one of the most ambitious examples of governmental cathedral thinking in modern history.

Thirty-five years after that sweltering July in Houston, RITE continues operating, still producing environmental research and technological solutions. The program reveals both the possibilities and limits of long-term institutional planning.

There's something profound about this kind of speculation: being compelled to plan furthest into the future precisely when we know least about what that future holds. The greater the time scale, the greater the uncertainty. Whether such planning represents human hubris, practical necessity, bureaucratic folly, ecological philosophy, or simply the mundane work of governance depends largely on one's perspective.

What remains, today, is the apparent urgency of the same question from 1990. The question is whether such comprehensive, long-term environmental planning is collectively achievable.

August 29, 2025—

Zenmai (Clockwork) - Susumu Yokota 横田 進 from Acid Mt. Fuji. 1994

A beautiful sound from Yokota that merges Japanese new age, house, and minimal techno and the birth of a new scene in Japan emerging during the Employment Ice Age, where the so-called "Lost Generation" came of age during the economic stagnation following the 1990s economic bubble bursting. Remastered on Sublime.

References

The Rice Thresher (Houston, Tex.), Vol. 78, No. 1, Ed. 1, Monday, June 4, 1990.

Climate Justice Museum, 'The Voice of a Changed City: How the 1990 Other Economic Summit Changed the Environmental Justice Movement in Houston', Climate Justice Museum, https://www.climatejusticemuseum.org/blog-posts/the-voice-of-a-changed-city-how-the-1990-other-economic-summit-changed-the-environmental-justice-movement-in-houston, accessed 29 August 2025.

Images

IDEA Extra Issue – The World’s 10 Poster Artists Exhibition. A catalogue of the exhibition held at Nihonbashi Takashimaya in 1982. It features 30 works by five of Japan’s leading designers, including Nagai Kazumasa, Tanaka Ikko, and Yokoo Tadanori, and Holger Matthies, and Milton Glaser, for a total of 300 pieces. Under the theme of “Protect the Green, People, and Earth,” 10 designers with unique personalities and talents competed, and the collection of works is overwhelming. Even a universal theme cannot be expressed universally because the qualities, styles, and techniques are completely different. Publisher: Seibundo Shinkosha

アイデア 世界の

ポスター

10人展Stills from C-SPAN footage of The Other Summit. From Houston Climate Justice Museum. 1990

More notes