Kohoutek

Image: Luboš Kohoutek talks with Skylab 4 astronauts from Johnson Space Center, Houston. 1974

Image: Skylab 4 astronauts confer via telecom with Earth.

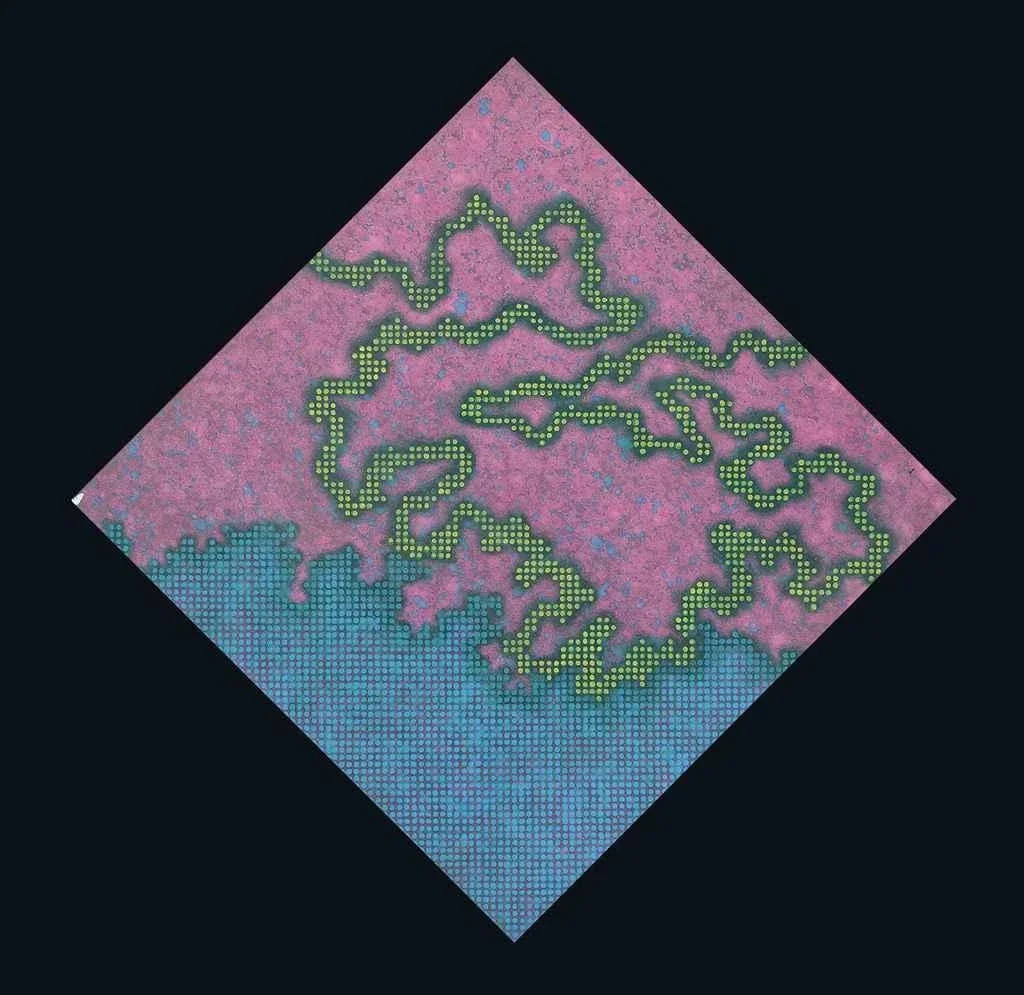

Image: Ant Farm at CAMH. 1973-1974

Winter 1973 delivered two Kohouteks, one a cosmic disappointment and the other a brilliant act of architectural theft. That year, the Comet Kohoutek, named for discoverer Luboš Kohoutek, was expected to be a celestial spectacle visible in daylight, outshining even Venus. William Safire, writing in the New York Times, predicted the so-called comet of the century would be one of the biggest, brightest, most spectacular astral displays that living man has ever seen.

By the summer of 1973, sales of telescopes quadrupled, religious fundamentalists interpreted the comet's arrival as being a harbinger of God, psychiatrists said the impact on patients had already been "profound", Carl Sagan was invited to The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson to discuss the new cosmic age, and comet-themed merchandise and apparel was in demand.

But when it finally arrived, Kohoutek proved far dimmer than expected. Bright enough to see, but far from the exuberant projections that had captured public imagination. Kohoutek became synonymous with spectacular disappointment.

The month the comet had been predicted to reach maximum brightness, December 1973, the art and architecture collective Ant Farm opened their own Kohoutek exhibition at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH). Alternately titled Exhibit of Visions of the Future, A Scan on Tomorrow, 20/20 Vision, and Visions 4-2MAR0, the wordplay in their printed ephemera was an obvious but brilliant appropriation: "KO - knockout, HOU - Houston, TEK - tech".

Ant Farm had formed in 1968 when Doug Michels, a Yale architecture graduate, met Chip Lord while guest lecturing at Tulane, where Lord was studying architecture. The two founded their collective in San Francisco, then eventually moved to Houston as visiting professors at the University of Houston. There, Michels and Lord planned free-form events such as trips to the beach to play with giant inflatables, a downtown scavenger hunt, and a sleepover in the Astrodome with parachutes suspended by helium balloons.

They weren't dropouts from serious practice but serious practitioners who had abandoned professional conventions. In California they had built big inflatable environments using cheap fans and polyethylene (picture inflating a plastic grocery bag, but at scale). Their hundred-foot-square "pillow" was used as the medical tent at the Altamont Speedway Free Festival in 1969.

As trained architects and artists, Ant Farm possessed something most futurists lack: the ability to draw, blueprint, and physically craft their speculations. While academic and professional futurists work with probability curves and scenario matrices, Ant Farm created architectural drawings, installation plans, and visuals that made abstract possibilities tangible. They could draft technical specifications for impossible (so far) buildings and hammer speculative futures into floor plans.

While astronomers and the media narrowed their calculations around a magnificent orbital and cultural possibility, and got it famously wrong, Ant Farm were considerably looser in their imagination. At CAMH they produced predictions saturated with play, creating tangible and gently ridiculous expressions of our relationships with American past, present, and future.

Their 20/20 Vision - Kohoutek exhibition folded time and inflection points together, mixing allegory and reality. A 1959 Cadillac convertible sat in the gallery, while visitors could look through round portholes into The Living Room of the Future and see an active video feed from Skylab, the United States' first space station, where, at the same time, astronauts might have been conferring over cosmic distances with a deflated Luboš Kohoutek.

Teleportation and biology fused in the museum presentation, and surveillance was imagined by the architects as a gland, part machine, part living organism, monitoring evolution. Their playfulness was genuinely strange, and never preachy. The Doll House of the Future in the exhibition hosted a colony of Barbie dolls with access to an experimental sperm bank, while all intelligence was imagined to be collected in a brain bank made of living tissue laced with electronic amplifiers controlled by insects (ants of course). Ridiculous, certainly, but not superficial.

"Any useful idea about the futures should appear to be ridiculous," says futurist and educator Jim Dator, because "what is popularly, or even professionally considered to be the most likely future is often one of the least likely futures". Ant Farm had by 1973 already established a consistent track record of being both ridiculous and prescient.

But the infinite expanse of "anything can be anything" futurism, especially for artists, is easy to get lost in. Ant Farm avoided this kind of total untethering. Unlike freeform hallucinations that treat the future as a blank canvas, they anchored wonderment to observable technological developments. In California, they practiced optimistic pessimism, reflecting their belief that too many architects were waiting to see what technology NASA and various defense projects would produce. In their Inflatocookbook they appealed for exchange between scientists, manufacturers, architects, and social administrators in investigating new material applications and technology.

Crucially, they avoided lecturing or hardening into total satire. Nothing in 20/20 Vision feels mean or proposes an overwhelming sociology assignment. Their invitation to visitors was to get on a warped freeway with them and steer through a constellation of emerging realities.

The Information Age was gaining momentum the year of their CAMH show. Electronic innovations, breakthroughs in data storage and display technologies, expanding satellite networks, and shifting cultural attitudes converged to fuel widespread anticipation about what was "just around the corner".

Information and its movement was the connecting thread between these developments, and theorist Marshall McLuhan's writings on mass-media intuited a collapse of traditional boundaries between here and there. Ant Farm positioned themselves not as detached critics but as engaged interpreters, responding to the new personal computing industry emerging in their own region.

Houston, where they found themselves working, had become America's clearest expression of flow-based urbanism. The first official document to guide the city's future was a thoroughfare plan put together in 1942, a mere three decades prior to the CAMH show. The future was rendered as traffic. Transportation remained the organizing framework for Houston into the 1980s, and growth revolved around moving people and things efficiently: freeways threading through subdivisions, the ship channel pushing material toward the Gulf of Mexico. Johnson Space Center and NASA, rocketing people to the moon and back, carried forward this logistics theme.

Ant Farm's work naturally drew from this car culture vocabulary. The 1959 Cadillac and line of gas pumps inside CAMH, their earlier Media Van projects, Truckstop Network (which proposed highways creating new information networks), and later on their Cadillac Ranch in North Texas (and maybe, too, their worksheets for the World's Longest Bridge and World's Fastest Turtle) all rearranged the language of transportation-aspiration.

The link between physical flows and information flows wasn't explicit, but it was there. "Image mobility will replace physical movement," predicted Michels in 1978. This position would lead him to co-found Universal Technology with artist Alexandra Morphett, a company that seems to have produced no actual products but instead toyed expertly with how information networks might reshape cities and, audaciously, the universe.

In nearby San Antonio, Texas, engineers Phil Ray and Gus Roche, who worked on various NASA programs, including the Apollo missions to the moon, founded Datapoint Corporation in 1968. Their ambition was to have a piece of the technological future, and they would do this by developing products that moved information around.

Datapoint existed to solve efficiency problems, the opposite of play in spirit and process. Their prototypes and terminals were things someone could respond to and build around. In Texas there began to be tangible and physical elements for techno-folk collage, and the future wasn't just an abstract possibility. In other words, there existed a new opportunity for artists, architects, scientists, or tinkerers to "hook in" and create relationships with change, rather than just commentary.

Enter Universal Technology, who, delightfully, convinced these serious-minded engineers to hire them for their Corporate Data Station project.

Universal Technology's core identity is not easy to decipher. On blueprints they called themselves The Creation Corporation, and they operated in an unusual domain where experimentation, pranking, techno-utopianism, and straight-faced entrepreneurship weren't mutually exclusive.

They called what they were doing "pre-enactment," a sophisticated alternative to random speculation. Their 1979 design for the Corporate Data Station described a structure that rehearsed the future of networked computing, including a Datavision media system of screens and audiovisual equipment, word-processing offices, and housing for networked Datapoint computers. Users could enjoy tangible, tactile interfaces and the whole thing existed in a nautical form, like the bow of a boat, made of aluminum tubes wrapped in lightweight nylon.

A cold reading might be that pre-enactment was an elaborate word that simply meant play, and the Corporate Data Station was just cubicles. The Data Station looked like a combination yacht and a space capsule, suggesting nautical movement and aerodynamic efficiency. A generous aesthetic gift to the work of word-processing contained within it.

It's tricky to surmise whether their plans to headquarter their company in the Philip Johnson-designed Two Post Oak Central building in Houston's Galleria district was serious or absurd: while simultaneously designing satellite-enabled workstations suitable for corporate contracts and factory production, they had a growing obsession with dolphin-to-human interchange and dreams of a watery interspecies "embassy" for dolphin-human communication. (Official dolphin embassy letterhead was printed). Later Michels would propose Bluestar, a glass space station operated jointly by humans and dolphins.

Image: Philip Johnson-designed Two Post Oak Central

Image: 2020 Vision at CAMH ephemera. 1974

Image: Ant Farm’s Dolphin Embassy

The connecting line was networking technology that would entirely reshape both human communication and work patterns, as well as our relationships with animal intelligence. Academics might now call this Animal-Computer Interaction (ACI), more-than-human design, or critical posthumanism. Universal Technology was experimenting with concepts decades before academic terminology formalized.

Universal Technology, skilled at image-making and branding, were valuable enablers and collaborators. Both companies understood that naming new or unproven technologies shapes how people think about them. Datapoint had its own adventure with terminology when, amazingly, they initially planned to call their ARCNet system "Internet," but switched the name just weeks before launch, worried that customers would reject something that sounded too complex.

Working alongside architect Richard Jost, Michels created the most precise and prophetic example of these combined skills through a private commission from Houston patron E. Rudge Allen. The project showed their approach to playing with the moment. Allen wanted to stay ahead of the technological curve. While Allen wanted to turn time into money, the architects turned Allen's money into a sofa that talked to space. Possibility actualized, and upholstered.

They called it a Teleportation Unit, alternately Media Room, and it combined computing, telecommunications, media projection, and comfortable seating. In blueprints it sits right next to an open floorplan kitchen, dining room, and living room. One of the first, if not the first, Apple II series computers in Houston is on the desk in publicity photos. The term teleportation unit captured what the technology promised (being elsewhere instantly) while making it sound like the future made real.

Image: Richard Jost / Belle Magazine. 1980

The unit essentially anticipated remote work, and would be one piece of the eventuality they imagined: thousands of cities connected to Eden Satellite systems. This built upon Ant Farm’s earlier proposal for an experimental city of 20,000 people between Dallas and Houston, which they presented at Rice University in 1972. The teleportation unit was a prototype for how people might live and work in such networked settlements.

When Ant Farm subtitled their CAMH exhibition Kohoutek, they were betting on cosmic spectacle. The comet was supposed to be the show of the century, and the architects couldn't have known it would fizzle. But they had grasped something special about scale and invitation. Like presenting a prospectus for a new city in Texas, spectacle, at any level, even anti-spectacle, resonates if it remains participatory rather than prescriptive. And they understood McLuhan: "The future of the future is the present, and this is something that people are terrified of.”

The future recedes relentlessly. Even the most astute targets recede and ambitions deflate in unpredictable ways. Astronomers plotted probable brightness, projecting a spectacular show. What they got instead was a lesson in the limits of prediction. The social obsession with Comet Kohoutek would later echo in Year 2000 Problem (Y2k) anxiety. Both are moments when collective anticipation far exceeded what came to be.

Houston, and Datapoint, learned this painfully. The year of Ant Farm’s CAMH show kicked off a Texas oil boom, peaking when one in every 20 commercial Bell helicopters sold on the continent were flying above Houston. When prices dropped to earth in the 1980s, the city was in such bad shape people facing foreclosure gave the banks the keys to their homes and walked away. Datapoint’s arc lifted them to a Fortune 500 company down to bankruptcy in 2000, after losing hundreds of millions of dollars in market value during a 1980s accounting scandal.

Rather than mapping futures from a distance, Ant Farm and Universal Technology give us clues about how to create relationships with emerging realities. The point is not that they had discovered a replicable methodology for futures thinking or even visualization. It is that they were actually good at play: genuine, unforced, and driven by curiosity.

This is harder than it sounds. A sleepover in the Astrodome is, in 2025, the stuff of corporate offsite dreams. The awkwardness of contrived ideation sessions and team-building exercises only highlights how naturally play and fun came to Ant Farm and the people associated with the collective. Wonder resists over-engineering.

Poetically, much of Ant Farm’s archives were destroyed in an unpredicted storage fire. Michels, who died in 2003, was still working on the future at the turn of the millennium, developing a hundred-year vision in a University of Houston seminar called Houston 2100, which addressed the city’s flooding problem. And Allen, the patron, died sitting in his Saarinen chair in the room where the teleportation unit had once promised he could be anywhere.

August 15, 2025—

Video: We Make Computers. Datapoint. 1978

References

Dewan, Shaila. 'Back to the Futurist'. Houston Press. 16 December 1999. https://www.houstonpress.com/news/back-to-the-futurist-6565939?showFullText=true.

Flyntz, Liz. 'Ant Farm's Visions for 2020: A Wilderness of Tomorrows'. Vesper. Journal of Architecture, Arts & Theory 3: Nella Selva | Wilderness (Fall-Winter 2020): 175-183. https://doi.org/10.1400/283007.

Lazowska, Edward D., Henry M. Levy, Guy T. Almes, Michael J. Fischer, Robert J. Fowler, and Stephen C. Vestal. 'The Architecture of the Eden System'. Department of Computer Science, University of Washington, Seattle, 1981.

Nakamura, Randy. 'The Architect as Corporation as Media: Doug Michels, Alexandra Morphett, and Universal Technology, 1978–1980'. In Play with the Rules: 2018 ACSA Fall Conference Proceedings, p. 159. 2018.

Oettinger, Anthony G. 'A Convergence of Form and Function: Compunications Technologies'. In The Information Resources Policy Handbook: Research for the Information Age, edited by Benjamin M. Compaine and William H. Read. MIT Press, 1999. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3771.003.0008.

Images

Dr. Luboš Kohoutek, discoverer of the Comet Kohoutek, is seen in the Mission Operations Control Room in the Mission Control Center during a visit to Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston. He is talking over a radio-telephone with the Skylab 4 crewmen in the Skylab space station in Earth orbit. Dr. Zdenek Sekania, who accompanied Dr. Kohoutek on the visit to JSC, is on the telephone in the left background. Dr. Sekania is with the Smithsonian Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts. NASA Identifier: S74-15064

The three members of the Skylab 4 crew confer via television communication with Dr. Luboš Kohoutek. This picture of the three astronauts was reproduced from a TV transmission made by a TV camera aboard the space station in Earth orbit. They are, left to right, Gerald P. Carr, commander; Edward G. Gibson, science pilot; and William R. Pogue, pilot. They are seated in the crew quarters wardroom of the Orbital Workshop. NASA Identifier: S73-38962

More notes