Options for Tomorrow’s City

Image: Lidji Design

Image: DMA

Options for Tomorrow's City was a process exhibition mounted over the winter of 1972/1973 at Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, in partnership with the Department of Planning and Urban Development of the City of Dallas.

A guide would take visitors through a maze, starting with the past, of course, to see how problems had evolved. Next they'd walk through today's Dallas (the Dallas of 1972), but experiencing it in a manner "very different from your everyday contact", according to the press release.

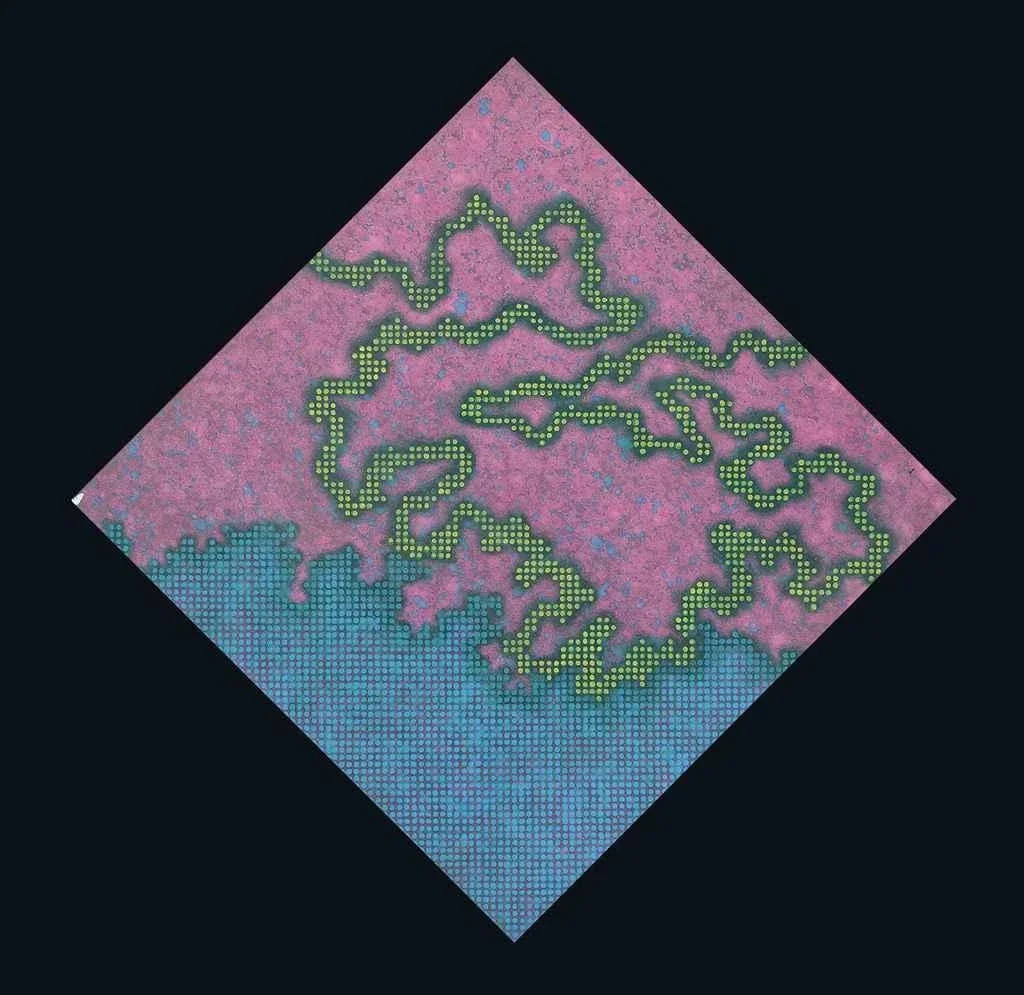

Getting deeper into the maze, a visitor was prompted to decide what kind of city they'd like to live in tomorrow, keeping a record of their solutions by placing stamps in designated sheets provided to exhibition visitors. The idea was the sheet would then become a picture window illustrating the kind of city you had designed, one that you could take home with you.

The final segment of the experience was to explore many different kinds of tomorrows and future environments, utilizing six big screen audiovisual displays, called "The Talking Stamp Map".

Without being able to see the video work, Options for Tomorrow's City appears to be relatively standard public engagement and planning research, with additive cultural authority in the museum space. Guides were members of the Department of Planning and Urban Development. Visitors were asked questions such as "Do you want more deserted inner city streets or more pedestrian malls?" and "Would you let water pollution be continued or stopped?" The bias built into such questions is obvious. Who advocates for pollution? This straightforward approach to foresight planning reveals something about how institutions believed citizens should engage with urban futures.

What I like about this moment is the backdrop: those in Dallas with the means and connections had the bright idea to link the museum with the planning department. This suggests a cohesion and functional exchange between cultural leaders and city governance that feels necessary from a purely progressive (in the sense of making progress) perspective. The collaboration implied a shared belief that futures-thinking could belong in public space, that citizens could meaningfully participate in designing tomorrow's city through guided interaction. (A more cynical interpretation might be that the design was a gimmick, a means to an end).

The whole effort becomes a little richer when considering what else was happening in the space. Alongside this civic exercise in democratic “museum futurology” was an exhibition celebrating Expositions of the 1930s. That earlier Dallas fair had imagined futures through monumental architecture drawing from archaic Greek, Mayan, and Aztec forms, blending technological optimism wrapped in ancient aesthetic authority.

This created a funky, and very 1970s, layering of eras and anticipation. There was also work very much of its moment being shown: artist Robert Graham was creating miniature worlds using small human figures positioned within plexiglass boxes and domes. His approach to scale created intimate universes where viewers peered down at tiny scenarios.

These contained environments, almost like mini pavilions, suggested more ambiguous relationships with futurity than the stamp-collecting literalism of the planning department. Where the civic exhibition promised agency through participation, Graham's sealed worlds questioned whether the future might be something we observe and who’s in control. The term “worldbuilding” comes to mind.

The retrospective celebrated past visions of the future wrapped in timeless architectural forms. Graham's figures, in transparent containers, suggested something more uncertain about human agency within the systems we construct to contain possibility. The civic exhibition assumed citizens can vote their way to better tomorrows through guided choice-making.

All three approaches had emerged from the same cultural moment, yet pointed toward entirely different relationships with time and change. Perhaps the simultaneous approaches to tomorrow is itself the most accurate representation of how alternative futures work: not as singular destinations but as complementary invitations.

September 24, 2025

—Image: DMA. 1972

Image: Robert Graham. Untitled. 1969

Images

Brettell, Richard R., NOW/THEN/AGAIN: Contemporary Art in Dallas 1949-1989 (Dallas, 1989) [Design: Lidji Design]

Robert Graham sculptures are plexiglass, wax and various materials. 11" x 18" x 30"

More notes